Pictured above, Gabriela Alvarez, nurse manager at Esperanza Health Centers

With a COVID-19 hotline and telemedicine systems, Esperanza Health Centers won’t let its patients fall through the cracks.

By: Ricardo Cifuentes, VP External Affairs, Esperanza Health Centers & Meghan Haynes

“Right now, our Latinx community is most vulnerable to COVID-19.”

This statement was among the closing remarks of Esperanza Health Centers COO Carmen Vergara during a May 6 televised press briefing, after she had outlined the unique, multifaceted factors that place Chicago’s Latinx community in a precarious place: jobs that doesn’t allow for working from home (WFH); multigenerational households that don’t allow for tiering risk by preexisting conditions or comorbidities; dense living arrangements that may not lend themselves to self-isolation.

As is the case in communities of color, the global pandemic is merely magnifying inequalities that already existed. Before COVID-19, many Latinx residents on the South and Southwest sides were already facing significant challenges accessing healthcare. Thus, Esperanza’s resolve to adapt, adjust and meet the challenges of this time has merely grown.

“Our patients, they already have so many things to worry about, this just adds to all that,” says Esperanza nurse manager Gabriela Alvarez. “So we have to be ready to take their calls and support them every day. And really, it’s just part of Esperanza’s mission.”

Two key components of Esperanza’s revamped work are its COVID-19 hotline, and the expansion of telemedicine services. The COVID-19 hotline was set up March 16th; Alvarez is one of the Esperanza nurses who’s been moved away from her typical nursing duties to staff the phone triage hotline full-time, taking in the fear, anxiety, and uncertainty that are overwhelming a community by giving people reassurance and solid medical guidance. She offers a glimpse into one such call, during which the caller “just burst out crying” by her fifth word.

“She’d tested positive in the hospital, she’d been self-quarantining, and she was struggling so much. She wanted to interact with her family at home, but she was terrified about it. She couldn’t find anyone to guide her,” says Alverez.

“I talked to her about her symptoms, what she was doing to self-isolate, how her family was doing. Reassured her she was doing great. But she needed more, so I scheduled her for a full telehealth visit with one of our medical providers. And I also set her up for a visit with one of our mental health counselors who could talk to her by video chat right in her home.”

Vergara calculates that Esperanza sees 350-500 patients each day via telemedicine. This is an essential outlet for a patient population in which she estimates 25 percent are undocumented, 52 percent of are uninsured, and 95 percent need or prefer to have care delivered in Spanish.

Within a few days of launching the hotline, Esperanza also set up outdoor COVID-19 testing tents at its two biggest clinics, in Little Village and Brighton Park. The organization refers about three-quarters of its hotline callers to visit a site for testing — as of story posting, Esperanza says it has tested nearly 5,500 individuals, with a positivity rate of 43 percent. Though the positivity rates have trended downward over time — from more than 50 percent in mid-May to less than 20 percent for these first weeks of June — the cumulative rate is still close to one of every two tests being positive. Currently, 47.9 percent of all Chicago COVID-19 cases are reported as Latinx*, and Latinx residents have comprised the majority of Chicago’s COVID-19 cases for many weeks now.

“There’s so much confusion and fear,” Alvarez says. “I do think that when people talk to a medical professional, and get the right information on how to reduce the risk of spreading the virus, how to practice social distancing, they tend to do it. But what about the people who have to work to survive? Maybe working under the table. They can’t stay at home.”

“And I’m surprised, although maybe I shouldn’t be, to see how many people don’t have a doctor, haven’t engaged in healthcare long-term. I spoke to someone today in his 30s, doesn’t have a doctor, never thought he needed one. Maybe this pandemic will make a big difference, maybe one of the ripple effects will be that people see how important it is to establish care. And they’ll follow through on that.”

As an Elevated Chicago steering committee and community table member, Esperanza is engaged in this work on all levels. It’s expanded its testing to include symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, and will soon begin contact tracing in its neighborhoods. Nurses like Alvarez will continue to take “call after call after call,” finding rewards in the rigor. COO Vergara will continue to work with Esperanza leadership to galvanize and coordinate resources necessary to continue testing and ensure that the organization will still be able to provide services for any and all who seek it.

Without Esperanza’s work, there would be a glaring hole: hampered coordination of resources; impeded and complicated access to tests (of which there is still an urgent and ongoing need, and the ability to increase and sustain testing in the immediate future and beyond is critical); and lacking interventions on behalf of Chicago’s Latinx community. The organization will not let its community fall into a void.

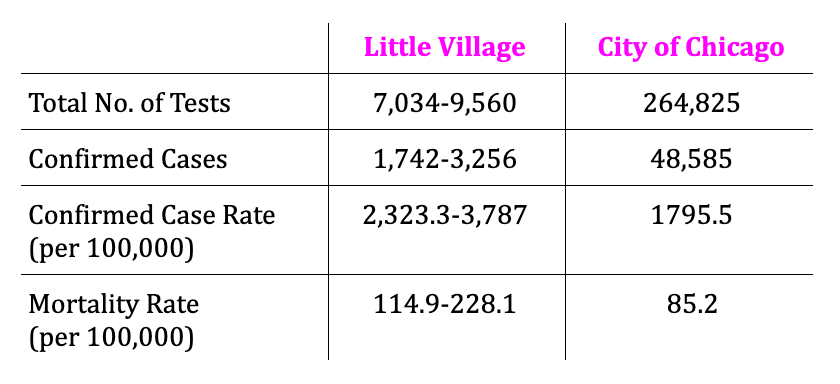

COVID-19 in the Pink Line California eHub

(as of June 9, 2020)

Above Table *Source: City of Chicago Coronavirus Response Center, “Daily Status Report: June 9, 2020”, using zip code 60623 to represent Little Village